by Berit Erickson

I’m not exaggerating when I say that my pollinator garden has changed my life. How can a garden possibly do that? Well, let me tell you…

January 2017 – the epiphany

We woke up one January morning to find the broken boughs of our cedar tree splayed on the street. For decades, this tree had screened our house from the traffic and pedestrians on our busy corner. Without it, we’d be left with a patchy lawn filled with dandelions and crabgrass. What could I do?

At the same time, the news was filled with foreboding – stories of political turmoil south of the border, perilous climate change, and “insectageddon.” But what could I do?

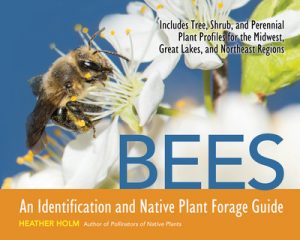

I distracted myself from the outside world with a stack of new and new-to-me gardening books. It had been years since I’d read any, and I was keen to learn about the new movement toward naturalistic design and habitat gardening. Bringing Nature Home,1 Planting in a Post-Wild World,2 and Bees: An Identification and Native Plant Forage Guide3 all begin with the depressing realities of habitat loss and its effect on birds, insects, and other wildlife. So much for escaping bad news!

I distracted myself from the outside world with a stack of new and new-to-me gardening books. It had been years since I’d read any, and I was keen to learn about the new movement toward naturalistic design and habitat gardening. Bringing Nature Home,1 Planting in a Post-Wild World,2 and Bees: An Identification and Native Plant Forage Guide3 all begin with the depressing realities of habitat loss and its effect on birds, insects, and other wildlife. So much for escaping bad news!

At first, I thought that habitat loss was just an American problem. After all, Canada has a lot of wilderness left. However, in southern Ontario, most wild spaces have been cut, bull-dozed, plowed, and paved. Some pollinators, like the Rusty-Patch Bumblebee and Karner Blue butterfly, are no longer found in this province. Habitat loss is considered the main cause of their disappearance.

Thankfully, these books also offer hope. Native flora and fauna have evolved together and are dependent on each other. We can help compensate for habitat loss by planting native plants in urban spaces.

That’s it! I would turn our front yard into a pollinator garden. I may not be able to solve the world’s problems, but I certainly can change my garden. I can also encourage others to change their yards. For the first time in a long time, I felt excited and empowered.

February 2017 – preparation

To keep the garden budget-friendly, I knew I’d have to grow plants from seed. Lucky for me, winter turned out to be a perfect time to start. Many native plant seeds need to go through winter weather in order to germinate – unlike the annual and vegetable seeds we usually plant in spring. I also planned to move or divide pollinator-friendly, non-native plants that I already had.

Finding Ontario native seeds in February wasn’t easy. Thankfully, Wildflower Farms, near Orillia, does offer them year-round. Now my new seeds needed a dose of winter weather. Typically, growers mimic winter by putting native plant seeds in the refrigerator for “cold, moist stratification.” No pretend winter for my seeds though, the Wildflower Farms website encouraged me to put the seeds in pots right outside in the snow! So I sat on the floor of our family room, filled Dollarama pots with Canadian Tire potting soil and planted dozens of seeds. I then shoved the pots into the snow in the backyard. My always tolerant and supportive husband built cedar frames topped with chicken wire to keep squirrels out of the pots.

I also decided to replace the lost cedar with a new tree, preferably one with high wildlife value. I contacted the city’s Trees in Trust program and chose a Hackberry tree. Although it won’t be the most beautiful tree, several kinds of butterflies use it as a host plant, birds like to nest in the witches’ brooms that can form on its branches, and its seeds provide winter food.

While I waited for spring to arrive, I continued to read everything I could find on native bees, butterflies, birds, and plants. Even though I had been an avid gardener for 20 years, I was shocked at how little I knew. I had no clue that most bees are solitary and make nests in the ground, in stems or other cavities. I didn’t know that most butterflies overwinter here as a caterpillar, chrysalis, or adult, instead of migrating like Monarchs. Even though I had had a bird feeder up for years, I had no idea that baby birds need to eat thousand of insects to survive.

Spring 2017 – digging in

As soon as the ground was workable, I began digging up the front lawn. What had I gotten myself into? I had a lot of weeds and turf to remove, along with old landscape fabric and the cedar roots that had grown into it. But I wasn’t going to turn back now.

I also turned the well-worn shortcut through our front lawn into a tidy path with layers of newspaper and mulch. The newspaper-smothering method worked very well, and I now recommend it for creating new pollinator gardens. Simply cover an area of grass with layers of newspaper or leaf bags, put soil on top, and wait for the buried vegetation to die off. If you do this in the fall, and plant seeds right on top of the soil, you can let mother nature take care of the cold, moist stratification during winter.

I felt self-conscious working so close to the sidewalk ripping up my lawn. With passing neighbours inquiring or casting puzzled looks, I decided to start planting as soon a possible by prepping and planting the garden one strip at a time. I also bought a “Pollinator Habitat” sign from the Xerces Society and installed it along the path in an effort to explain my project.

I had read about some native plant gardeners receiving complaints from neighbours and municipal officials, so I carefully designed the new garden and strive to keep it well-maintained. I use a fixed colour scheme of white/blue/yellow/orange/red for flowers, locate shorter plants close to the path and taller plants farther away. My garden plan is also greatly inspired by Piet Oudolf’s4 popular, naturalistic gardens, like the High Line in New York and the Lurie Garden in Chicago. Although my yard now looks very different from neighbouring yards and gardens, much to my relief, passers-by have only given me positive feedback – they think it is pretty and they appreciate my good intentions.

Later in the spring, I also added more mature native plants bought at the popular Fletcher Wildlife Garden native plant sale, from Beaux Arbres Native Plants in Bristol, Quebec, and from Fuller Plants nursery in Belleville.

A tremendous success

My corner pollinator garden has been a tremendous success. Right away, there were so many bees in the garden! Bees even visited pussy willow and goldenrod as I took them out of the car trunk and placed them on the driveway.

A Tricolored Bumblee and a tiny black and white bee on Virginia Mountain Mint (click for a larger view)

Starting early in May, mining bees nested in the ground and collected pollen from our new pussy willow shrub. Shortly after, large bumblebee queens visited the crabapple tree, and flew back-and-forth close to the ground searching for nest sites. Tiny carpenter bees dug out coneflower stems to make nests. Leaf-cutter bees cut oval-shaped pieces of leaves, and carried them to their nests between rocks in a dry stone wall. A male wool carder bee hovered around guarding a patch of smooth beardtongue, while the females scraped balls of fuzz from pearly everlasting leaves to line their nests. Dozens of worker bumblebees covered the anise hyssop, drinking nectar, and noisily buzz-pollinated Japanese anemones.

Butterflies visited flowers for nectar and the host plants I grew to feed their caterpillars. We found American Lady caterpillars on our patch of field pussytoes only a couple of weeks after we’d planted them. Black Swallowtail caterpillars laid eggs on parsley and fennel. In a grand finale, dozens of Monarchs and Painted Lady butterflies stopped by to rest and eat during their late summer migration.

In the garden’s second year, we saw even more insect diversity: colourful beetles, dragonflies, strange-looking (non-threatening) wasps, hummingbird moths, fireflies, and different butterflies that I had never seen before. You just never know what you’ll see in the garden!

Teaching an old gardener new tricks

During my pollinator garden research, I learned that a surprising number of conventional gardening practices are actually harmful to pollinators. After years of gardening, I’ve had to retrain and become more laid back. I felt like I was learning to garden from scratch all over again.

During my pollinator garden research, I learned that a surprising number of conventional gardening practices are actually harmful to pollinators. After years of gardening, I’ve had to retrain and become more laid back. I felt like I was learning to garden from scratch all over again.

First of all, most insects are no longer considered pests in my garden. If I see an unfamiliar bug, I now try to identify it, instead of immediately squishing it. It is actually true that if you leave aphids alone, ladybugs and other predatory insects will take care of them. It probably goes without saying, but I don’t use any pesticides, herbicides, or fungicides any more.

I’ve also had to learn to leave some messiness in the garden. I no longer cover the garden in wood mulch because ground-nesting bees cannot use mulched areas. I now rely on native ground covers – “living mulch” – to shade the soil and suppress some of the weeds. In the fall, I leave the leaves in the garden because butterflies and queen bees will overwinter underneath. Eventually, the leaves break down and fertilize the soil naturally. I don’t deadhead or cut back plants in the fall either. I leave this task for the spring, leaving stems 15-inches long as ready-to-use bee nest sites. Plant material is left in the garden too, providing shelter for insects and nest materials for birds.

Much to my relief, native plants don’t require the same coddling as many introduced plants. I don’t have to amend the soil for them to thrive, as long as I plant them in similar conditions as they’re found in the wild. Plants that are found in the shady loam of a forest are planted under trees, and others that grow well in sun and clay soil go in a similar spot in my yard. Native plants don’t require special winter protection either. Instead of spending time helping the plants survive, I spend it thinning or potting up seedlings, or dividing vigorous varieties to share with other gardeners.

More than just a pollinator garden

It turns out that our new garden isn’t just a pollinator garden, it’s a bird garden too! The serviceberry flowers that feed bees in the spring provide berries for hungry Cedar Waxwings and Robins in June. The anise hyssop that was covered in bees in the summer, is covered in Goldfinches eating its seeds in the fall. Other seed heads that remain in winter provide food for Juncos or Chickadees.

We’ve enjoyed the bird visitors so much that we have added a hedgerow of berry-producing shrubs to our backyard, and even put in a circulating pond and stream this summer. With the hot, dry weather, many bird families visited the stream to drink and bathe. Such fun to watch. Our teen-aged son even says that he enjoys watching birds more than playing video games!

The garden is also an outdoor science classroom for our whole family. When we see a new insect or bird, we pause to observe it and learn more about its role in our backyard ecosystem. We’ve become so interested in the natural world around us that we now frequent trails and parks on weekends and joined the Ottawa Field-Naturalists Club. We no longer suffer from the “nature deficit disorder” that’s described in Last Child in the Woods.5

And the pollinator garden is a place to meet and teach others. Since I started the garden, I’ve met many neighbours who stopped to chat and ask questions. So many seemed interested in learning about pollinators or in starting their own gardens, that I created a brochure to leave out for when I’m not there. Over 150 brochures have been taken so far. I’m also getting ready to teach a class on what I have learned. I want to help bridge the gap between interest in pollinator gardening and actually creating one.

You can do it too

So you see, the pollinator garden has actually changed my life in many ways.

For the first time, I really feel like I am making a difference for wildlife and for the health of our environment. It may be a small difference, but it is a tangible one. I can see right in front of me that I’m now providing food and shelter for hundreds of bees and butterflies and dozens of birds. I would never have imagined that my new pollinator garden would be so full of life. After all, we live just a few blocks from a busy, 6-lane road, gas stations, and a grocery store. We’re surrounded by a school field and houses with large lawns and few gardens.

If more people, like you, turn some unused lawn into a native plant garden or adapt an existing garden, the impact of these individual gardens will add up. I saw this strategy in practice during a summer vacation in Toronto. On the street where we stayed, almost every postage-stamp-sized yard contained milkweed and other flowers for pollinators. When planted side-by-side, these tiny gardens added up to a street-sized habitat full of bees and Monarchs.

I often hear native plant gardeners say: “plant it and they will come.” It really is that simple. My garden is living proof. Go ahead, you can do it too!

References and inspiration

- Tallamy, Douglas. 2009. Bringing nature home: how you can sustain wildlife with native plants. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon, USA.

- Rainer, Thomas, and Claudia West. 2015. Planting in a post-wild world: designing plant communities for resilient landscapes. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon, USA.

- Holm, Heather N. 2017. Bees: an identification and native plant forage guide. Pollination Press, Minnesota, USA.

- Oudolf, Piet. High Line – Lurie. Hummelo, Netherlands

- Louv, Richard. 2008. Last child in the woods: saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

For further inspiration, be sure to visit Berit’s web site, where she not only provides information on how to Create your own pollinator garden but also blogs about the creatures she finds in her garden.

Berit joined our network earlier this fall. During conversations and a site visit with her, her enthusiasm and knowledge quickly became evident. Like her, we want everyone to make this kind of difference – save the pollinators!

I enjoyed your article so much. My gardens started from a new water line being installed by the Rural Water coming in. That has been probably 30 yrs ago and I have given up that 50 ft patch and only have a few Sumac trees and rocks, but I still maintain a rather large country garden that keeps me in shape. I am 74 and just can’t give them up. It is the most rewarding and relaxing time when I am pulling weeds or planting something else. God’s antidepressant medication!!! Birds singing, bees humming and a new discovery of insect or plant.

[…] © Wild Pollinator Partners […]