by Sandy Garland, presentation slides and identifications from Jessica Forrest, photos by Barry Cottam

What is a bee? How do you distinguish them from look-alike flies and wasps? How do they live?

On May 18, Jessica Forrest, bee researcher from Ottawa U, answered these questions and more before a rapt audience at the Fletcher Wildlife Garden’s resource centre.

A bee is “a kind of vegetarian wasp,” she explained. They eat nectar and pollen and collect these foods for their young. Most wasps prey on other insects to feed their young; some wasps also drink nectar and, in doing so, pollinate the flowers they visit.

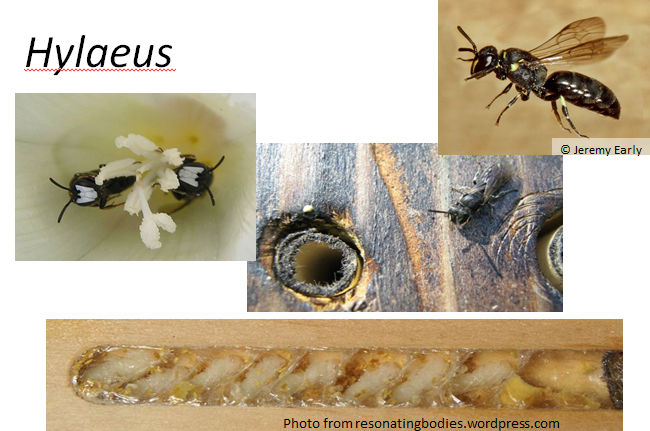

Bees have branched hairs – the better to hold pollen – although some are relatively hairless. For example, bumble bees have so much hair, they look fuzzy, whereas masked bees have very few hairs, and carry pollen inside their body.

Wasps also have little hair, often a thin “waist,” and the ones we see most often have long folded wings.

Many flies mimic bees and wasps, but they have only 2 wings (instead of 4), very large eyes, and very short antennae.

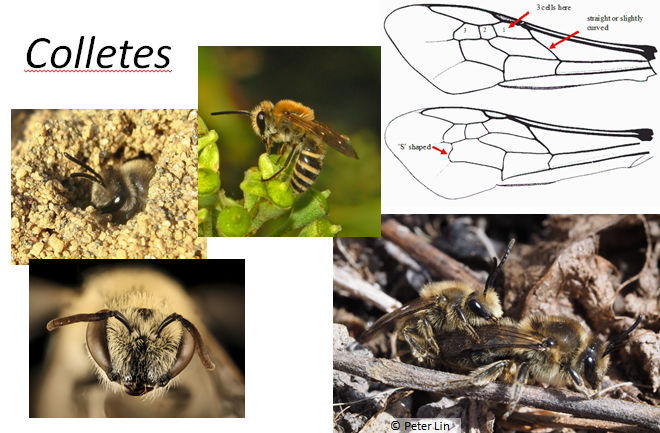

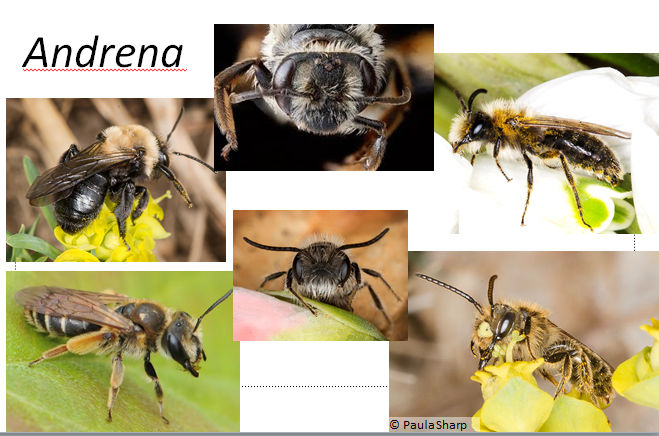

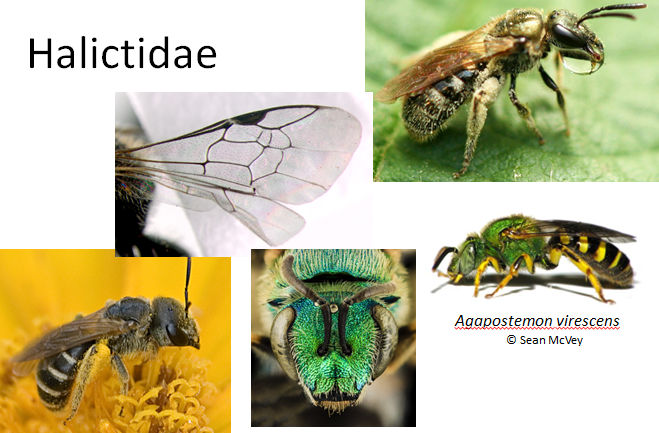

Jessica showed us photos of a number of species in the main groups of native bees: bumble, mining, cellophane, masked, sweat, leafcutters, orchard (or mason), and cuckoo bees. Learning their relative sizes, habits, and life cycle as well as any distinctive physical features helps with identification in the field.

Most people recognize bumble bees, as they are big and they are active all summer and into the fall. Large queen bumble bees are often seen in spring, looking for a spot to make a nest and foraging for pollen and nectar. After her first children become adults, the queen mostly stays in the nest and lets the offspring collect food.

Andrenids, or mining bees, are completely solitary. Females mate, then dig tunnels in bare spots. They collect pollen, store it in small chambers in the tunnels and lay an egg in each.

This large group is also called masked bees, as males have white or yellow markings on their face; females have smaller markings. They are relatively hairless and instead carry pollen in their crop.

Commonly called sweat bees, because they are attracted to the salts in our perspiration, these bees are usually seen in summer into fall. Many species in this group are bright green. They nest underground.

Leafcutter bees emerge from winter hibernation in June. If you see perfect circles cut out of leaves in your garden, celebrate the presence of these bees, who use the pieces to form and line their egg chambers.

Mason bees are often the first bees to emerge in early spring. They are also called orchard bees because they pollinate our fruit trees as they go about their “business” of reproduction.

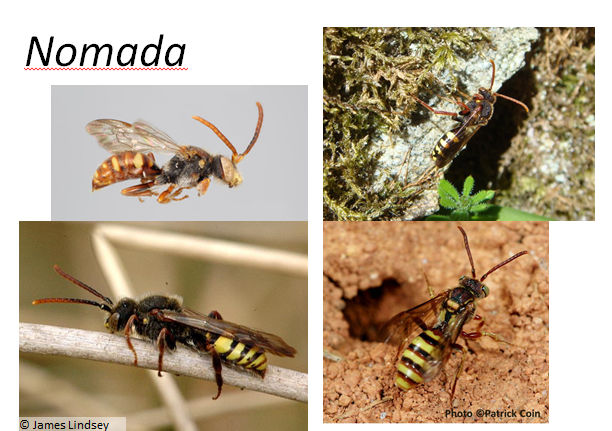

Nomada are also called cuckoo bees, because, like the cuckoo bird, they lay eggs in others’ nests instead of building their own. Easily mistaken for wasps, with their narrow (for a bee) waist and yellow and black stripes.

After Jessica’s talk, we had a chance to practice our new knowledge. Although the sun was uncooperative – disappearing just when we needed it most – we found some bees in the FWG’s Backyard Garden.

Female andrenid bee in the genus Andrena, but we are not sure which species. See how the antenna are a bit longer than the diameter of her head and her eyes are spaced apart (so NOT a fly). Her rather thick body means she’s not a wasp either. The pollen on her hind legs is the clinching characteristic here – definitely a bee!

We found small holes in a patch of bare soil in our Backyard Garden. Watching closely, Barry photographed this female andrenid bee emerging to gather more pollen and nectar to stock the underground chambers where she will lay eggs.

Dandelions provide nectar and pollen to pollinators early in the season when not much else is blooming. Here, tiny sweat bees – halictids, specifically Lasioglossum, subgenus Dialictus – are enjoying a communal buffet. Note the green colour!