by Lydia Wong

This post is an excerpt from updates sent to those following Lydia’s research project on the effects of urban warming on cavity-nesting insects. If you’d like to receive these updates, please contact Lydia at lwong014@uottawa.ca.

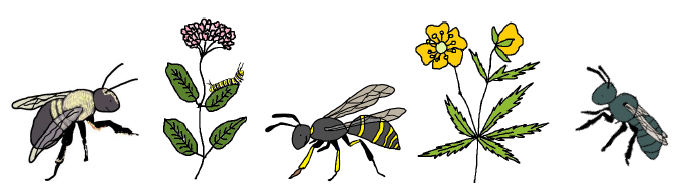

With the weather finally cooling down, bee and wasp comings and goings are tapering out. Other than the odd male bumblebee awkwardly clinging to an aster here and there, things seem to be getting very quiet in the bee and wasp world. And yet, somehow, come spring and summer, there they are again – crawling, flying, feeding, chasing, mating, prey-catching, egg-laying, nest-building in full force.

What are they doing so quietly in these cold months?

I’ve been thinking and reading a lot of about the bee/wasp world’s “quiet time.” What goes on in the nests of these insects come fall and winter? And how do the eggs somehow end up as bees and wasps come spring and summer?

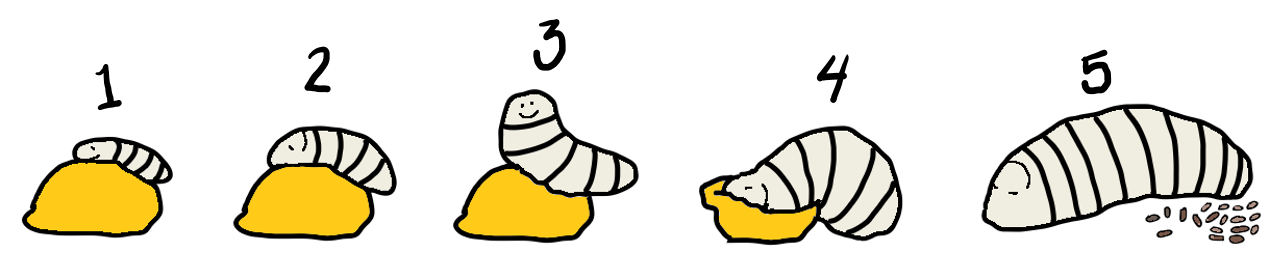

Photo from Joan and June’s garden in Toronto, showing a grass-carrying wasp (Isodontia) going from egg to cocoon. Photos courtesy of June D’Souza.

Here’s a little summary…

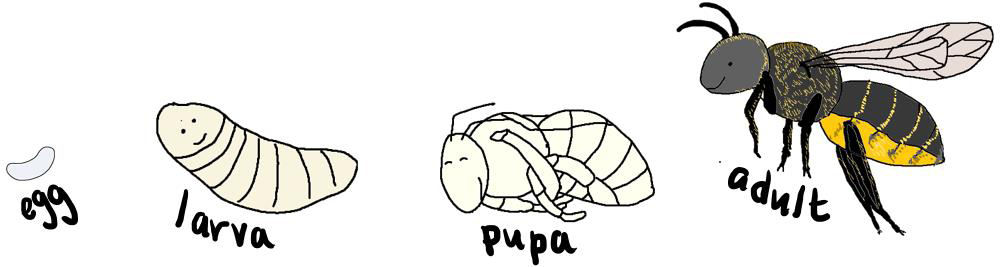

Roughly, the bee/wasp lifecycle has four distinct stages.

The amount of time bees and wasps spend in each life stage varies depending on the species and their environment, so the times I describe below are approximate (and are mostly what I know from reading about and working with cavity-nesting species).

Egg

Eggs usually hatch within 2–4 days after being laid. While in the egg, juvenile insects are already starting to develop jaws and other body parts. The little guys break free from the egg by wriggling their bodies and/or using teeth-like spines on the sides of their bodies.

Bee egg in pollen (left) and wasp egg suspended at the top of nest cavity (mom was probably working on filling the cell with food when photo was taken). Eggs are pretty tiny, often 1.5–3 mm in length. Both photos courtesy of Isabel Rivera.

Larva (the white squirmy worm stage)

Once hatched, bee and wasp larvae progress through four or five growth stages (instars), growing a little bigger and shedding their outer skin (integument) each time. At some point (usually growth-stage 2), larvae start eating their food provision. They also start pooping around stage 4 or 5. All of this eating, growing, and pooping generally takes another 1–2 weeks. See video of a squirmy mason bee larva.

Once the larva finishes eating the prey or pollen provided by their mother, they spin a cocoon. The cocoon is made out of strands of saliva with bits of sand and poop mixed in. As the larvae spin their sandy, poopy saliva-y cocoons, they also move around their cell, orienting themselves such that their heads are pointing towards the nest exit.

At the right is a leafcutter bee cocoon (sleeping bee inside). This cocoon was about 1 cm in length and weighed a little over 100 mg.

At the right is a leafcutter bee cocoon (sleeping bee inside). This cocoon was about 1 cm in length and weighed a little over 100 mg.

Pupa (teenager bee/wasp)

When I’m around kids, I often refer to the pupae (singular = pupa) as “teenager bees and wasps.” By the end of this stage, bees and wasps have typically reached their mature size and have developed antennae, eyes, legs, and other parts that we see in adult insects flying about our yards. But, until the end of this stage, the pupae appear white in colour and don’t really move around. Essentially, they’re almost adults, but just aren’t quite there yet.

Some bee and wasp species spend the winter as “late-stage” larvae, waiting until the spring to pupate and emerge as adults (e.g., leafcutter bees – Megachile species). Other species winter as pupae or even as fully developed adults. The latter tend to become active earlier in the spring as they don’t have much growing to do come the new year (e.g., mason bees – Osmia species, and mining bees – Andrena species).

Adult

Adult bees emerge in the spring/summer – males first, followed by females. (Male bees/wasps are typically laid at the front of the nest while the females are laid at the back). The insects mate, construct nests, visit the flowers in our gardens, and the cycle restarts!

I am constantly reminding myself that most of the time, I really only see bees and wasps in one out of four life-stages. In general, (if not for bee/wasp hotel structures with transparent plastic panes), I am in the dark when it comes to the life stages bees and wasps spend in the dark! As someone who spends lots of time thinking about these insects, it’s humbling to know how much I still don’t know about my six-legged friends :-).

Lydia Wong is a graduate student working with Dr. Jessica Forrest at the University of Ottawa. Her research explores the impacts of warming and drying climates on wild pollinators. She spends the summers studying this in the Colorado Rockies but can also be found nosing around the concrete jungles of big cities on the lookout for city-dwelling bees and wasps. She is currently working with citizen scientists in Toronto and Ottawa to explore the effects of urban warming on cavity-nesting bees and wasps.

This is an excellent blog which I learned a lot from. The photos are amazing and I love the illustrations and captions too. And I agree that it is humbling to realize how little I know about bees and wasps, so I look forward to following more of what you share with us about your research. Thank you.