By Lydia Wong

This post is an excerpt from updates sent to those following Lydia’s research project on the effects of urban warming on cavity-nesting insects. If you’d like to receive these updates, please contact Lydia at lwong014@uottawa.ca.

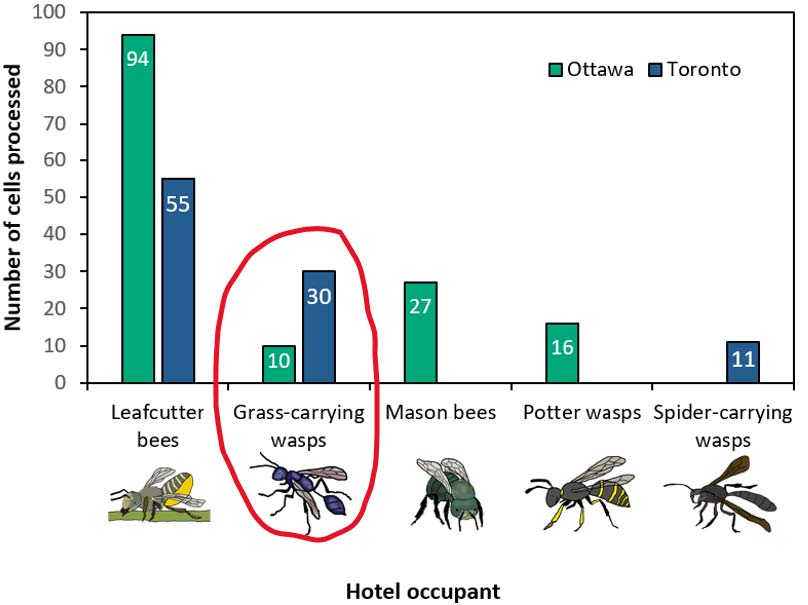

After leafcutter bees (Megachile species), grass-carrying wasps (Isodontia species) were the next most numerous occupants in the hotels this summer.

There are a couple grass-carrying wasp species in Ontario and the Northeastern U.S., but my guess is that all of the the grassy-looking nests we had in the hotels this past summer were from one species, the Mexican grass-carrying wasp (Isodontia mexicana; Dr. Rob Longair who is also hosting hotels might know better). Despite their name, I’m pretty sure this species is native to North America (recently introduced in Europe).

Mexican—-Grass—-Carrying—-Wasp… is a bit of a mouthful. I’m going to refer to these little critters as “MGC wasp” for the rest of this letter. Here’s a photo of a MGC wasp nest from Miriam’s garden in Toronto (PC: Miriam)

And a photo of a female MGC wasp checking out a cavity in Coach Tom’s garden in Toronto. She didn’t end up nesting in the cavity, but this gives an idea of how big they are.

Nest structure

Most cavities contain 3 to 5 little chambers ‘cells’, each containing a number of little baby crickets (baby wasp food) and a single wasp egg.

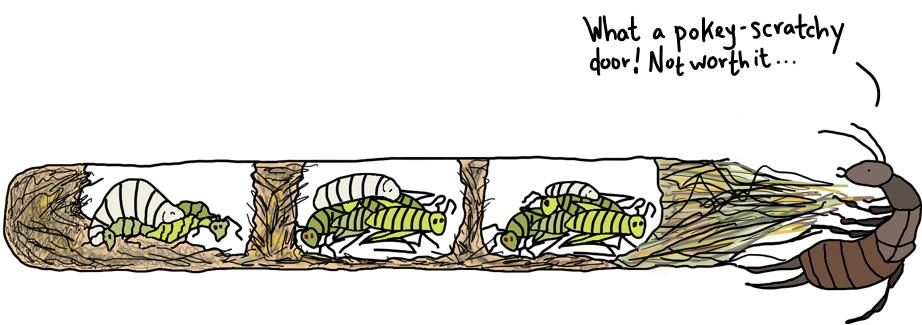

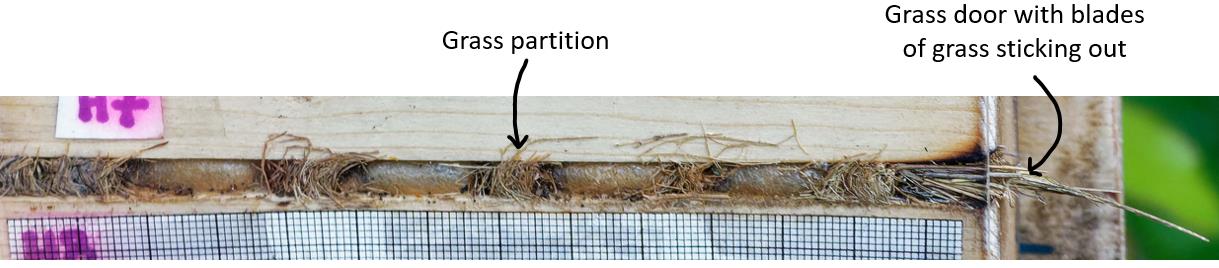

The cells are partitioned by fine grass clippings woven tightly together. The ‘door’ of the nest also consists of tightly-woven grass clippings, followed by some longer blades of grass stuffed together in a tuft and that often sticks out beyond the nest entrance.

Photo by June D’Souza from Joan’s garden (Toronto)

Photo by June D’Souza from Joan’s garden (Toronto)

Here’s a video of an MGC wasp nest being opened up in the lab (cocoons material feels like felt… hence the cocoon sticking to my very dry fingers).

I lost a number of leafcutter bee nests to opportunistic earwigs this summer, but didn’t lose a single MGC wasp nest. I can’t help but wonder if this pokey-grassy nest style helped play a role. Maybe grass is harder to get around compared to leaves.

The cricket food

Female MGC wasps seek out their prey (baby tree crickets and katydids), sting them with their stingers to paralyze them, and carry them back to their nests, inserting them into the cells head first.

A paralyzed cricket is:

- not going to thrash about while being transported by the female wasp

- stays nice and fresh until the baby MGC wasp hatches from its egg and is ready to eat (a dead one would probably rot)

MGC moms have really thought it all through

The baby wasps hatch from their eggs, and eat their cricket food, starting by sucking out the juicier cricket bits first and leaving the chewier and fibrous bits (wings, head) for later, or else not eating them at all. A couple nests I opened contained lots of leftover cricket food in the form of very dehydrated heads and wings.

Based on the nests I looked at this year, uneaten cricket food was more common in nests constructed late in the summer – nests constructed early contained little to no leftovers. I’m thinking that by the end of the season, most crickets are grown up (no longer baby crickets), making them a little chewier and harder to digest. Hence there being more leftover food scraps in the late nests (I think!). I did notice that the size of the crickets in Caroline’s hotel (Toronto) which was constructed late-September contained much larger cricket food compared to nests constructed earlier in the summer (e.g. Joan’s, below).

Late MGC wasp nest: Sept. 26 at Caroline’s place in Toronto (crickets are > 1 cm long! Photo by Caroline).

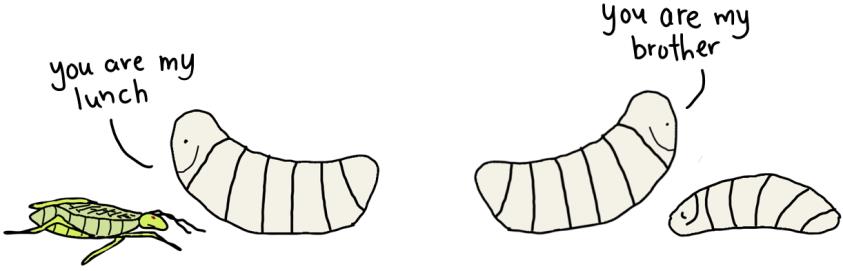

There is one other grass-carrying wasp species in Toronto, though not in Ottawa (this is according to a hasty iNaturalist search) – the Brown-legged grass-carrying wasp (Isodontia auripes). That said, the grassy-structured nests in the hotels were unlikely to have belonged to individuals of this species. Brown-legged grass-carrying wasps don’t partition their nest cavities with walls. Instead, females lay all their eggs in a single cavity stocked with many baby crickets. Studies have shown that the baby wasps in these nests are skillfully able to differentiate between the baby crickets (their food), and their siblings (who obviously should not be eaten!) despite the absence of walls. Nests are dark places and I imagine baby wasps and baby crickets rank similarly in terms of squishiness… so this ability is quite something!

Lydia Wong is a graduate student working with Dr. Jessica Forrest at the University of Ottawa. Her research explores the impacts of warming and drying climates on wild pollinators. She spends the summers studying this in the Colorado Rockies but can also be found nosing around the concrete jungles of big cities on the lookout for city-dwelling bees and wasps. She is currently working with citizen scientists in Toronto and Ottawa to explore the effects of urban warming on cavity-nesting bees and wasps.