by Maria Sievers

WPP’s final garden tour of the 2025 season took place at L’ecole Trille des bois, a bilingual public school with the Ottawa Carleton District School Board in Ottawa’s Vanier neighbourhood, with a heavily concentrated Waldorf philosophy/pedagogy.

Bumble bees seldom sting; the males can’t. Lydia Wong was able to introduce some pollinators close up. Photo by Sandy Garland.

We met on an overcast Saturday morning on an asphalt-covered soccer field between the two major buildings. We were welcomed by Eugenie Waters, chair of the parent school yard committee, another parent volunteer, and a teacher. Lydia Wong graciously agreed to be on hand as our “bee expert” and she again managed to delight her audience and find some interesting insect life, such as some assassin bugs in a compromising position.

During our tour, Eugenie told us about the history of the school’s outside yard. Initially a paved parking lot, it was “depaved” when the school adopted its Waldorf philosophy. Waldorf schools advocate lots of outdoor education, which is why many such schools are located near farms or forests. Even in this very urban environment, the teachers are able to take advantage of the nearby Richelieu Forest for regular nature exploration, but they also rely on the school gardens to teach curriculum-related materials. Instead of focusing on educational concepts, the school encourages experience first, from which an understanding of concepts will later naturally develop within the child. For instance, the grade 3 teacher host told us she is introducing “bees” in her curriculum right now and uses the garden to show her class living creatures, their behaviour, and habitat.

As parents are encouraged to participate actively in the school’s life, the parent council and principal were very supportive when the school yard committee presented its garden project and applied for a City of Ottawa Environmental Grant in 2022. Eugenie, who spearheaded the project, reported on the paperwork involved, but eventually they received $4200 and used it to buy soil, mulch, shrubs from Ferguson Nursery, and plants from Fletcher Wildlife Garden. Surprisingly, no concerns were raised by parents about the possible appearance of bees and their potential to sting.

Luckily, some semi-raised beds were already in existence, even though they contained no plants and the soil was hard. Massive planting took place by a group of dedicated parent volunteers, and for that first summer (2023), one family a week was assigned to water the new seedlings. This summer, with no watering, the beds show hyssops, false sunflowers, various goldenrods, and shrubs, such as Grey Dogwood and Ninebark. One bed containing fragrant sumacs has proven to be the most resilient of all. As Eugenie explained, the challenge now is to observe which plants fail to survive and to replace them with the most resilient.

Maintenance and observing what works and what doesn’t is now a key concern: with around 680 kids using the school yard daily, an ongoing challenge is the trampling of plants and incursions into plantings. The volunteers have gone through various iterations of fencing (including livestock fencing – dangerous metal parts when it disintegrates) to protect the plants. The current version of 2 by 2 wooden posts with drill holes at two levels and connected by rope seems to be working so far. Plantings leave room for some areas designed for special project teaching, such as planting seedlings in the spring.

Simple post and rope fencing has proved useful in keeping plants in low beds from being trampled. Photo by Sandy Garland.

As far as the plantings go, the committee has adopted an approach of “consolidate and defend,” which translates into rescuing threatened plants, putting them together in clusters and then fencing them for a better chance of survival. They found that fragrant sumac, which turns a beautiful red in the fall, is the most resilient shrub in the yard.

The school gardens consist on one side of a series of semi-raised beds along the central playground yard, which is mulched and has a little hill for climbing in its middle. On the other side, the yard is fenced in by chainlink and bordered by little roofed semi-huts and wooden logs. They tried to grow grapevines on the chainlink fence, but those were whipper-snipped by the school and did not survive.

Eugenie expalined how rain used to run off from the paved part of the schoolyard (where she’d pointing) down this slope, which it turned to mud. A raingarden to the right of the photo now retains and absorbs most of the water. The custodian is a big fan. Photo by Nora Lee.

As we continued our walk around the perimeter of the school yard, we arrived at Eugenie’s self-proclaimed greatest success: a rain garden. This side area of the school has a paved pathway along the building, but in the past every rainfall flooded the space between the pathway and chainlink, washing off of soil and mulch down a retaining wall into the side entrance to the school. Eugenie followed the City of Ottawa’s recommendations for creating a rain garden and in 2023, together with four other volunteers, dug out a circle of about 8 feet diameter to a depth of about 8 inches and filled the hole with layers of sand and mushroom compost. The space is now a lush “mini-forest”-type planting of Downy Serviceberry, towering Joe-Pye Weed and several giant hyssop species. Not only is there no more runoff, but it a very grateful janitor no longer has to clean up all the mud that was previously tracked into the school.

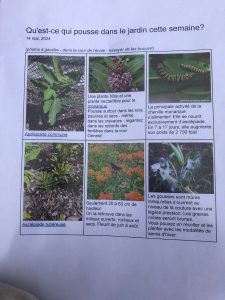

What’s growing here this week? Click on the image to find out about a few of the plants and the creatures that use them.

The dull weather didn’t stop foraging bumble bees on the day we toured the garden. These are busily feeding on hyssop plants in the rain garden.

We finally arrived at the last area of the committee’s purview: a stretch of garden formerly dominated by weeds and goutweed and exposed in full South sun. Eugenie organized three groups of Grade 5 students to remove goutweed and they seem to have succeeded. The strip along the school wall is now filled with native plants. This is the area of the school yard where the committee plans to plant at least four native trees, since their most recent grant application to the City of Ottawa’s Tree program was only recently approved.

In terms of education, Eugenie also developed a colourful handout demonstrating what is growing in the school gardens and distributed them to the teachers for them to share with their classes.

Finally, Eugenie reported that twice a year, in the spring and in the fall, a yard cleanup is organized. Sometimes only a core group of 4-5 parent volunteers – or sometimes up to 10 – show up to pick up garbage, sweep mulch off the asphalt, and fix fences. All in all, Eugenie says that the success of the school garden is largely due to having had a good start, with some beds already mulched, a pre-existing and committed school yard committee, and the Waldorf expectation that parents are supposed to be engaged in school activities.