by Berit Erickson

Once I had created a successful pollinator garden of my own [see Berit’s Corner Pollinator Garden], I began to see prime locations for similar gardens everywhere. One spot that I had been eyeing up was the vacant vegetable garden at my son’s elementary school, Churchill Alternative School. Each spring, it was enthusiastically planted, but struggled on its own after the student gardeners left for the summer. A low-maintenance, mostly-native perennial garden would be a perfect replacement.

I wasn’t the only person who had new ideas for the school’s vegetable plot. In April 2019, the school council asked if I would help create a butterfly garden. Of course I would!

What should we plant?

My first task was to come up with a list of suitable butterfly plants for this sunny, dry location. We needed two kinds: nectar-rich flowers to feed adult butterflies and host plants to feed their caterpillars.

Native plants are essential, because native insects have co-evolved with these plants. Over time, butterfly caterpillars adapted to the chemical composition of specific native plants in order to digest them – now, they can only eat these plants. For example, Monarch butterfly caterpillars can only eat milkweed – no milkweed means no Monarchs. Different kinds of caterpillars can only eat other, usually native, plants. The Fletcher Wildlife Garden’s Gardening for Butterflies page has a list of host plants for butterflies found in the Ottawa area.

For the school garden, I decided to include host plants for a few butterflies that I consistently find in my own garden: milkweed for Monarchs, Fennel for Black Swallowtails, and Field Pussytoes for American Ladies. These butterflies are all common in urban habitats.

To choose nectar plants, I consulted a few familiar lists, such as the Xerces Society list of Monarch Nectar Plants: Great Lakes, and the Monarch Watch Plants for Butterfly and Pollinator Gardens. There are lots of possibilities, so I again focused on plants that butterflies visit in my own garden. It is important to include a variety of nectar plants to ensure blooms from spring to fall.

Since native plants take a couple of years to mature, I also included some annual nectar plants. Annuals grow and flower quickly, so they would feed butterflies and fill in gaps in the garden while the native plants establish.

It has to be beautiful, too

I have never designed a garden for anyone else. I knew the school garden would have tremendous potential to teach children, as well as inspire parents and neighbours to create their own butterfly gardens. The school garden had to be beautiful, as well as functional.

I have never designed a garden for anyone else. I knew the school garden would have tremendous potential to teach children, as well as inspire parents and neighbours to create their own butterfly gardens. The school garden had to be beautiful, as well as functional.

As a design starting point, I used the cheerful colour scheme in a poster, Supporting Monarchs, from the Wisconsin Monarch Collaborative. The poster includes pink, purple, blue-purple, orange, and yellow flowers. I chose local native plants and annuals in those colours, plus a few white flowers.

A super-sized garden plan

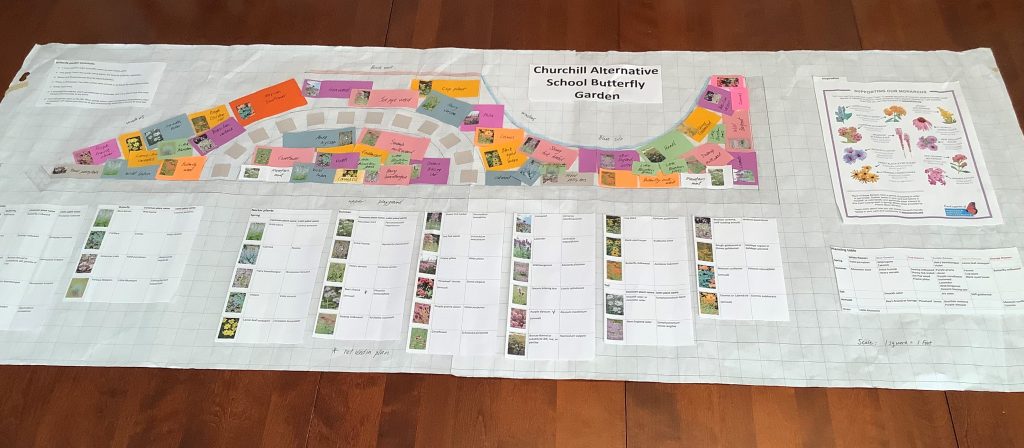

I made a garden plan to sort out exactly which plants we needed, how many, where we might get them, and how much they’d cost (for a school council budget request). In fact, I made a huge 1.5-metre garden plan. It could then be displayed on a school wall, so teachers, students, and parents would see it, and hopefully get excited about the new garden. (See Garden plan and plant list.)

I measured the space, including the location and height of windows (so I didn’t block them with tall plants). The garden is a large, oddly shaped, raised bed; it is about 9 metres long, and varies in width from 0.5 to 2.5 metres. I added a path so everyone could enjoy the garden up close without damaging plants, and to make maintenance easier. I used coloured pieces of paper that matched the flower colours, and arranged them on the plan to distribute the colours and make pleasing combinations. The tallest plants would go in the back against the brick wall, and the shortest ones at the front edge.

Growing and finding the plants

Now, where would we get the plants? Buying all the plants for the garden would have been too costly. Luckily, I had already started growing some native plants for the school’s annual spring plant sale, so I could provide a lot of them for free. Since many native plant seeds require a period of cold temperatures in order to germinate, I put the seeds outside in pots for the winter. I bought seeds from Beaux Arbres Native Plants, Wildflower Farm, and Botanically Inclined.

Students later grew the annuals from seed. We bought the remaining plants at the Fletcher Wildlife Garden native plant sale (first Saturday in June), and the Beaux Arbres native plants stall at the Westboro Farmers’ Market. By growing plants from organic seed and buying from native plant growers, we ensured that none of our butterfly plants had been treated with harmful pesticides.

Planting day

With the plan and plants ready to go, the Churchill teachers, students, and parent volunteers took over. Planting day, on June 3rd, was far from ideal — it was about 10°C with some drizzle.

First, the path was marked with bamboo stakes. Then, planting began at the back near the brick wall, and gradually progressed forward to the edge. This strategy reduced the chance of newly planted seedlings being stepped on. Finally, mulch was added around and between plants to retain moisture. (Eventually, Field Pussytoes and Common Violets will spread between plants to act as a “living mulch.”) The crew tolerated the weather and worked hard – all the native perennials were in the ground. Due to the unusually cool weather, the annuals weren’t planted that day. Contrasting-coloured mulch was later spread to delineate the path.

As a safeguard, a bamboo stake and twine fence was added around the entire garden to protect the tiny plants. Removable “gate” sections were placed at the path entrances to allow easy access.

The Churchill Alternative School butterfly garden adorned with a beautiful, and helpful, mermaid (27 June 2019).

For the rest of June, it rained regularly. The plants were thriving, but they were still small. We just had to wait for the garden to grow and butterflies to find it. And they did!

Summer watering and weeding

In July, volunteers watered the garden once a week. Since the school was open for camps, it was easy to access the hose. However, in August, with the core volunteers on vacation, the garden was left on its own. Despite the hot, near-drought conditions, the native plants still looked good, but a few of the annuals died. Crab grass spread everywhere, but an emergency weeding session took care of it.

Back to school

By the time school began again in September, the garden was filling in and blooming profusely. It was also attracting migrating Monarchs and Painted Lady butterflies, bumblebees, and other insects.

A view of the entire garden. Students made the Mason Bee house (with the white roof) using instructions from Wild Pollinator Partners. The enormous sunflower showed up on its own (2 September 2019).

I know children can be fearful of insects, so I wanted to introduce them to the harmless, interesting, insect visitors they might see. I created a PDF called Can You Find Me? describing the ones that frequented the school garden. Also, the Get the Kids OUTSIDE Facebook page has a useful guide to Helping Kids Overcome Their Fear of Bugs.

A few Monarch caterpillars were donated and raised in enclosures inside the school early in September. They were later released in the butterfly garden to start their journey to Mexico.

In October, students gathered seeds from the garden to sell at the school’s Christmas craft sale. A whopping 150 packets of native plant seeds were sold. There will be a lot of happy butterflies and bees in the neighbourhood.

Future changes

Based on the butterfly garden’s first year, we plan to make a few tweaks:

- Install a rain barrel on one side of the garden so volunteers can water even when the school building is closed. To water with the hose, it had to be carried outside, hooked up, and dragged over to the garden. A key was also needed to turn on the water. A rain barrel will be a simpler and eco-friendly alternative.

- Become a Monarch Waystation and install a Waystation sign.

- Grow native plants and annuals for the school’s spring plant sale: in progress.

- Control the Common Milkweed that was planted in the garden several years ago. It has spread a lot and popped up in all sorts of unexpected, undesirable places. It will be a constant battle to keep it from overtaking the garden. While we can pull out the unwanted stems, the deep root system will remain. Red Milkweed Beetles found their way to the school garden, and since their larvae eat milkweed roots, perhaps they will help us control the Common Milkweed. Swamp Milkweed and Butterfly Milkweed are much better choices for urban gardens.

- Discourage uninvited insect guests, like the ones that caused a crisis right before school began in September. While the garden was ignored in August, aphids infested the Common Milkweed. Aphids excrete honeydew, which attracted every European Paper Wasp in the neighbourhood. I ended up cutting the Common Milkweed to the ground and put it into leaf bags. (I first checked the plants for Monarch caterpillars.) Removing the honeydew made the wasps disperse to look elsewhere for food. Thankfully, when school started, they were long gone. By checking the garden weekly throughout the summer, we can easily control aphids by squishing them, and letting Ladybugs eat any we miss. We should also buy or make a wasp trap, just in case.

- Increase the proportion of native plants. There wasn’t enough time last year to grow native plants from seed specifically for the school butterfly garden, so we ended up using what we could get. This year, we can add a few more native nectar and host plants to replace some of the annuals that didn’t do so well in the summer heat.

- Create a weekly volunteer sign-up to distribute the maintenance work. Although many parents expressed an interest in helping out, only a core of experienced gardeners did most of the work. We need to harness people’s enthusiasm and help everyone participate. We will set up a system for volunteers to care for the garden one week at a time, from spring to fall. To do this, we’ll need to provide a bit of training and reference materials, so everyone knows what to do, when to do it, and how to do it.

- Shift primary responsibility for the garden from a teacher to the school council to reduce the teacher’s work load and to ensure longevity and continuity, regardless of staffing changes. Again, documenting butterfly gardening basics and maintenance procedures will allow parent volunteers to take care of the garden.

Create your own butterfly garden

The Churchill Alternative School Butterfly Garden was surprisingly easy to create and was also surprisingly successful, even after just a few months. I often tell people that if I can create a pollinator garden in my yard, anyone can do it. The school’s new garden proves that this success is repeatable, regardless of your location and gardening experience.

I encourage you to make a butterfly garden at your home or school. Here’s a PDF of our garden plan and plant list, to get you started. Like I always say, “plant it and they will come.”

Berit Erickson is an active member of the Wild Pollinator Partner network. Check out her web site to find out how she created her own Corner Pollinator Garden. It’s filled with observations, information, and advice for helping you help pollinators.