by Sandy Garland

Collecting seeds for the Canadian Wildlife Federation’s habitat restoration project on October 20 was fun (see Collecting seeds with CWF), but now those thousands of seeds had to be cleaned.

Once again, WPP helped publicize the event, and some of our partners showed up at the Fletcher Wildlife Garden last Sunday (December 8) to help.

Large pieces of light-coloured paper make a good work area – easier to see the seeds. Tin plates or various bowls hold the seeds. Photo by Jennifer Line.

Holly Bickerton, who is helping the CWF create pollinator habitat along roads and rights-of-way, gave a slide presentation on the the project. She showed us the four 2019 sites: two near Lanark, one at Green’s Creek, one in a hydro cut off Riverside Drive.

She has been monitoring these and reported success, although not immediate. Some of the perennial wildflowers they sowed take several years to mature, and she had to crawl on the ground to see the tiny first-year plants. Restoration requires patience!

In 2020, the CWF will be building on their successful partnerships – with the municipality of Lanark, the National Capital Commission, and Ottawa Hydro – and create more test sites. Thus the need for more seed and our help preparing it for planting.

An ordinary sieve can be used to quickly separate Black-eyed Susan seeds from their seed heads – just requires a lot of shaking. Photo by Jennifer Line.

Jennifer Line then showed us where the seeds had been collected, which species, and how they had to be cleaned. Cleaning involves removing stems, leaves, other debris, and seed pods (not the seed coat, just the container that holds many seeds together and could prevent them from growing).

For small quantities of seed, it’s best to do the cleaning when collecting. But if you need large quantities – or the weather is unpleasant – it’s easier and faster to cut the whole top of the plant and do the cleaning later.

Some seeds, especially spring flowering plants require considerable preparation, including removing fleshy parts and subjecting them to alternating cold and warm moist conditions. However, the seeds we were working with were dry and we simply had to find the best way to separate them from debris.

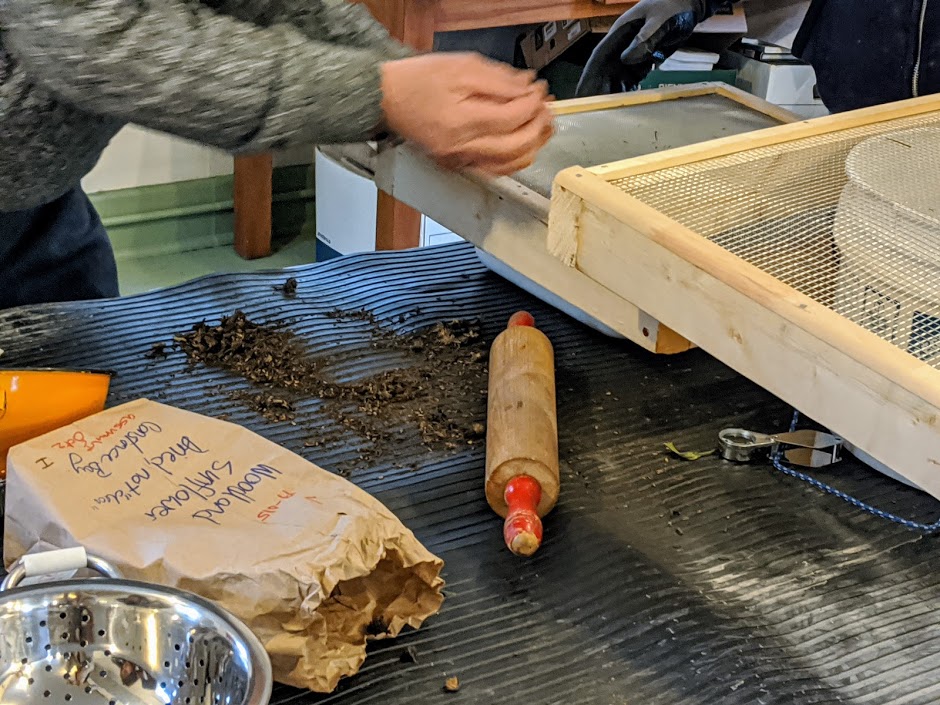

A rolling pin can be handy to crush open tough seed pods, then debris can be strained out using an appropriate-sized mesh. Photo by Li-Shien Lee.

Equipment included common kitchen tools, like sieves, rolling pins, and bowls. Jen brought along wooden frames with various sizes of mesh to screen out stems and leaves allowing seeds to fall through. Alternatively, sometimes the seeds stay in the sieve or on the screen and fragile debris can be crushed to fall through the holes. Again, lots to learn and every species is different.

A minor emergency occurred when one of us opened a bag of Fireweed seeds and their silky parachutes starting carrying them up into the air. Fireweed seeds are extremely tiny and the slightest air current can carry them away. Jen quickly closed the bag and fastened it shut.

In contrast, Evening Primrose seeds form inside very strong hard cases. Each one has to be opened and the seeds teased out.

Even the debris is useful. Because it might still contain some seeds that we were unable to separate, Jen kept the “garbage” in separate bags to plant next spring in different test plots.

Cleaning Grass-leaved Goldenrod seeds, which are too small to grab by their fluff, means pulling out leaves and stems (discarded in bowl at left) then painstakingly rubbing the seeds off the seed head, then lifting them off the heavier debris. Photo by Li-Shien Lee.

Once the seeds are clean, they’ll be delivered to the Ferguson Forest Tree Nursery where most will be subjected to cold, moist stratification. That’s a way to simulate what happens in nature, where most seeds lie on damp soil under the snow for the winter. During that time, chemical reactions occur inside the seed, which help it count down to spring. In April or May, warm temperatures and sometimes also light tell the seed it’s time to grow.

By the end of the afternoon, almost all the seeds were cleaned, packaged, and labelled. Coffee and poppy seed cake kept us working, and great conversation kept us interested.